The Great White Shark: Understanding A Misunderstood Ocean Giant

Great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) are often depicted in pop culture as fearsome ocean predators, and while they are apex predators, their role in marine ecosystems is complex and crucial. This article aims to provide comprehensive insight into the great white shark, touching upon its biology, behavior, conservation status, and the critical role it plays within the marine ecosystem.

Taxonomy and Physical Characteristics of Great White Sharks

Classification and Evolution

Great white sharks belong to the Chondrichthyes class of fish, which includes other sharks, rays, and chimeras. They are part of the Lamnidae family, an evolutionary lineage that has thrived in oceanic environments for millions of years. Great whites share a common ancestor with prehistoric megatooth sharks, but they have adapted distinct traits over countless generations.

Anatomy and Morphology

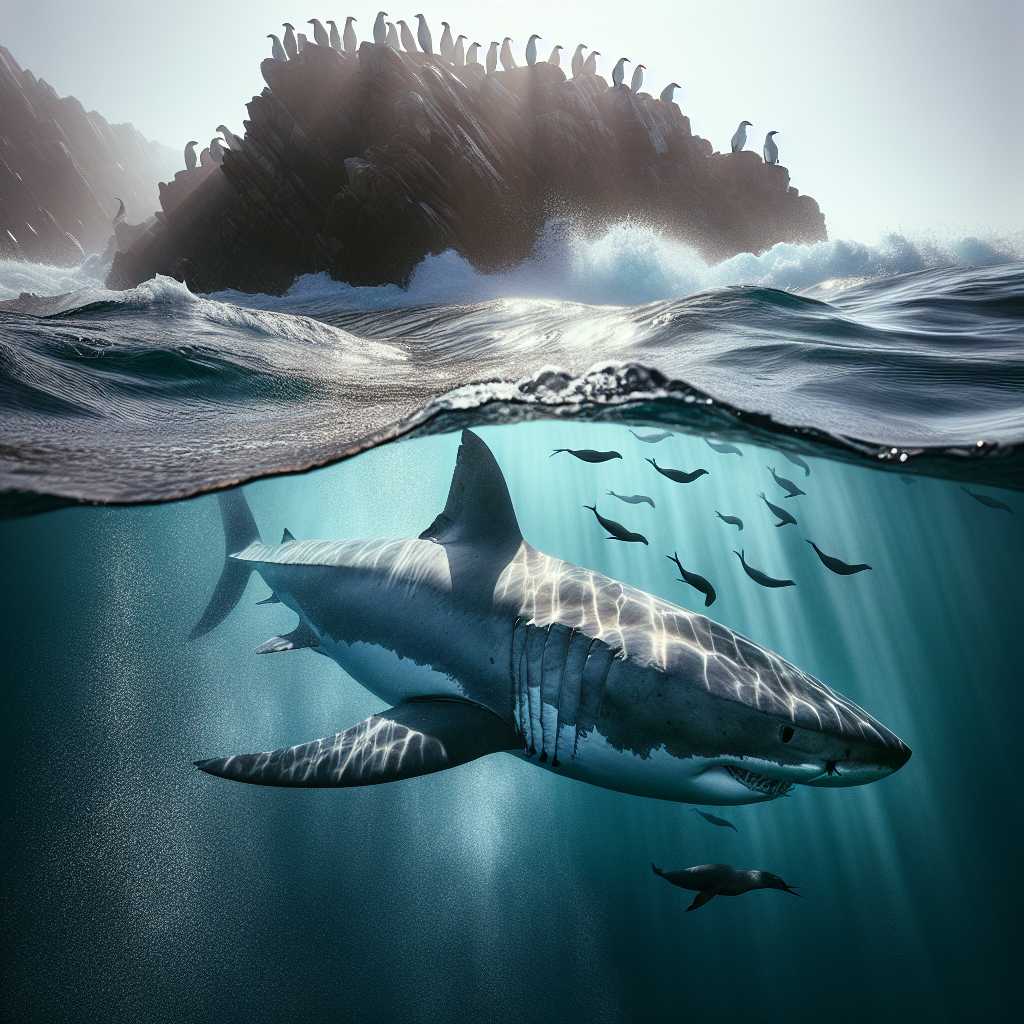

Adult great whites typically measure between 15 and 20 feet in length, although specimens exceeding this range have been documented. Males usually weigh around 1 to 2 tonnes, with females being larger. The morphology of the great white shark is perfectly adapted for their predatory lifestyle. They sport a torpedo-shaped body for streamlined movement through water, powerful jaws with several rows of serrated teeth designed for hunting marine mammals and fish, and a robust tail providing impressive propulsion speeds that can surpass 60 km/h (37 mph) in short bursts.

Their skin is a unique grayish-white camouflage called countershading; dark on the dorsal side and lighter on the ventral side to blend with the ocean depths when viewed from above and with the surface when seen from below.

Sensory Systems and Communication

The sensory systems of great white sharks are highly sophisticated. They can detect minute electromagnetic fields generated by other organisms thanks to special receptors called Ampullae of Lorenzini. Their sense of smell is also exceptionally acute, enabling them to identify blood in the water from miles away.

Great white communication is less understood, but they exhibit body language such as jaw gaping or pectoral fin lowering to express aggression or dominance. Vocal communication is absent as sharks lack vocal cords.

Great White Shark Behavior and Diet

Hunting Strategies

Their hunting techniques are a testament to their intelligence and adaptability. Great whites usually employ an ambush strategy: attacking from below at high speed which often propels both shark and prey out of the water in spectacular breaches.

Dietary Preferences

Seals, sea lions, and small toothed whales constitute their preferred diet, but they will also eat fish, including smaller sharks, rays, and carrion if necessary. As apex predators, great whites play an essential role in controlling population sizes of these marine animals, maintaining balance within their ecosystem.

Migration Patterns

Great white sharks are known to migrate across vast oceanic distances. Tagging studies have shown that individuals can traverse thousands of kilometers for reasons such as searching for food or breeding grounds. Their migration patterns still possess mysteries that researchers continue to investigate.

Human Encounters and Shark Attacks

While infrequent compared to media representation, shark encounters occur. It is believed that most shark attacks on humans are cases of mistaken identity, where a shark confuses a human for its usual prey due to poor visibility or curiosity. Many efforts to reduce these interactions focus on understanding shark behavior and educating the public about swimmer safety practices.

Conservation Efforts for Great White Sharks

Threats to Their Survival

Great white sharks face threats from human activities such as targeted fishing (for jaws, teeth or as trophies), bycatch in fishing nets, habitat destruction, and the impacts of climate change on ocean conditions.

Conservation Status

This species is listed as Vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Legal protections have been implemented in many parts of their range including national laws in countries like Australia, South Africa, and the United States under statutes like the Endangered Species Act.

Research and Protection Programs

Ongoing research projects aim to better understand great white’s life cycles, behaviors, and habitats to inform conservation strategies. Many non-profit organizations work on preserving marine biodiversity by advocating for protective legislation and engaging with fisheries industries towards more sustainable practices.

Protection efforts can also be supported by eco-tourism—picturesque shark cage-diving operations educate visitors on shark conservation while simultaneously contributing financially to these endeavors.

Education and Moving Forward

Great white species conservation is closely linked with broader ocean preservation battles like combating overfishing and protecting coral reefs. Public education campaigns raising awareness about their crucial role occupy an important place alongside scientific research in shaping a sustainable future for great whites and ocean ecosystems alike.

Notes

Image Description: A great white shark swims just beneath the ocean surface near a group of seals resting on the rocks above. Its dorsal fin breaks through the water’s surface while sunlight pierces the waves around it, highlighting its countershaded skin and formidable silhouette.